HOW GENERAL ABACHA 'REBUFFED' MANDELA

01/27/22, Kayode Soyinka

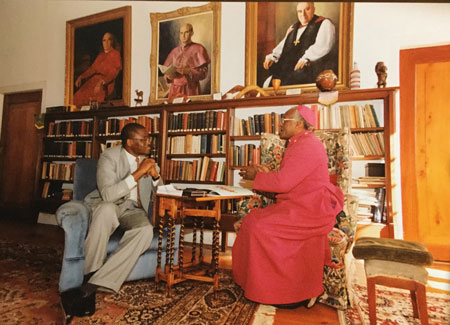

The confrontation between President Nelson Mandela's Special Envoy and Nigeria's Head of State is revealed for the first time in this interview with Africa Today. "They sounded just like apartheid Afrikaners...I didn't know whether to laugh or cry," says Desmond Tutu. The first Black Archbishop of Cape Town and Nobel Peace Prize winner also tells of his meeting with Chief Moshood Abiola in detention and recalls highlights of his own leading role as an Anglican Churchman battling against the evil of apartheid. Today, he is a "watchdog" over the new government. *

Africa Today: You went to Nigeria recently as President Mandela's Special Envoy to mediate the political crisis there. But before going into that. I want to take this opportunity to discuss South Africa with you - especially your personal role in bringing about the huge changes, most importantly those in recent years. Many people seemed to find contradiction in the role you were playing: a Christian cleric and at the same time a militant champion of Black people. Was there a time when you sat back to think, when you confronted yourself and then decided you could no longer stand by with folded arms while Black people were suffering?

Tutu: l don't think I had any sudden Pauline conversion. l had been working for the World Council of Churches in something called the Theological Education Fund when I was introduced to Latin American liberation theology and came to realise just how dynamic are the scriptures when it comes to confronting situations of injustice. When I returned to South Africa in 1975 - I had been invited to become Dean of Johannesburg - it became clear that God was giving me a platform which I should use to articulate the aspirations of the people. I was the first Black Dean and one of the remarkable things was that the press seemed to want me to succeed. So, l got quite considerable coverage, which was important for telling our story.

Africa Today: But at that time, you still could not be described as a radical person, in the mould of other rejectionists the world over. Did you play that role out of the conviction that God is a considerate God, who cannot tolerate suffering or be against the poor?

Tutu: I suppose some of those descriptions apply; some people might call us radical, but I don't think that applies to challenging the injustice and oppression of a system that was saying: "You're not important" or "You're not as important as other people who have a particular racial quality or characteristics." The Bible enabled one to reply: "Nonsense! Your worth, your importance is not determined by some intrinsic attribute'' and then to go on to explain that God would be against suffering. Not that He would necessarily stop it, but He seems to have shown, through the Bible that He had a bias: He was a God who is always on the side of the weak, of the small, the "unimportant" ones.

That was a tremendous thing to be able to tell people. Equally tremendous was the impact of being able to tell them: "Whatever they do to you, however they treat you, it does not alter the fact that, for God, you are someone of infinite worth. Whatever may be the case now, however powerful the government may be militarily and in all other kinds of ways, be assured that victory is going to be ours."

When freedom was going to happen was not in debate. Even to the government, we said to their face: "You have lost. You may he powerful now but that doesn't say anything about the eventual outcome." That is how we campaigned, and we would say to our people; "If God is for us. who can be against us? "

Africa Today: You became more and more vocal, especially the moment you became the first Black man to be ordained Archbishop of Cape Town. That prestigious position must also have given you a powerful platform, which the apartheid authorities could do nothing about.

Tutu: After becoming the Dean of Johannesburg, I became a bishop, and from 1978-1984, general secretary of the South African Council of Churches. I think that was the period when I became most vociferous. But I didn't sort of wake up in the morning and say: "OK, now I'm going to fix them today; this is what I am going to say and do." One reacted to the things they were doing. One didn't even try to be consistent. I even felt sorry sometimes for their ineptitude. They did such silly things, like when they took away my passport on a Thursday morning thinking that, because the next day was Good Friday, there would be no communications, and no one would know. But no sooner had they done it than it was all over the world.

On another occasion, about 50 of us ordained clergy went from Bloemfontein to Johannesburg for a demonstration. It was a very small procession to the John Forster police station where they were detaining one of our members. If the authorities had ignored us, our little procession would have gone to the police station, sung a few hymns, handed in our petition - and they could have thrown it in the dustbin the moment our backs were turned. But what did they do instead? They stopped us bang opposite the offices of the major newspaper in Johannesburg and we were being bundled into the police van, there were all these journalists looking on. Again, in next to no time, it was on the wires right around the world. We couldn't have organised better publicity ourselves.

The government got very obsessed with the South African Council of Churches and hated our programmes for supporting the families of political prisoners. We had a fund which I controlled as secretary general. We used it to pay the legal cost of people being held prior to appearing in political trials. Finally, they set up a commission to investigate us. They thought it was going to find out that we had enriched ourselves or that we were carrying on what they would have considered subversive activities. After about two years, when the commission's report eventually came out, they found nothing, and we were entirely vindicated. I said the government had ended up with a lot of egg on its face.

That was in 1984. That same year I was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Africa Today: Winning the Nobel Peace Prize gave you a potent weapon. It made you virtually untouchable by the apartheid regime.

Tutu: It all helped enormously. It was very heart-warming, a great encouragement. It wasn't awarded to me in my personal capacity, but as the representative of the South African Council of Churches which was considered to have carried out a significant ministry of reconciliation and witness.

But it also served as a warning to the perpetrators of evil, injustice and oppression. To the upholders of apartheid, we would say: "The world is watching you. Be careful." And to their victims we would say" The world is on your side. The world is supporting you."

And, of course, when you've won the Nobel Peace Prize, you suddenly turn into an oracle overnight. Things you've been saying for donkey's years suddenly acquire a new importance and everybody is dancing attendance on you. It served in a way to open doors that have been closed. For instance, up to that point President Reagan was not particularly interested in seeing me. But when I got the Nobel Peace Prize, I didn't ask to go to the White House, he invited me. But it was important because one was again able to put forward some of the things our people would have liked to have said.

Credit Adil Bradlow

Africa Today: As soon as Mr. Mandela was released from prison you stepped aside from political activities. You seemed to be telling the world that the Church cannot stand aside in abnormal situations. But now it could resume its normal role?

Tutu: We have been very fortunate in many ways. I never wanted to be actively involved in the way that we were when our leaders were in jail or in exile. I said clearly at the time that I was an interim leader. There were things that one was doing that which, in a normal society, would not have needed to have been done by a Church leader, but by politicians. But we were living in abnormal times. We had to comfort our people because often there were massacres and there were many funerals. We would go into these situations seeking to pour balm on people's wounds, trying to console, and encourage them to sustain their morale.

But as soon as the political process was normalised with the release of Nelson Mandela and others, with the exiles allowed to return home and the political organisations that had been banned made legal again, then there was certainly no cause for me to be addressing political rallies across the country. That was something that could now be done by politicians.

But we were still involved politically. We would never become apolitical because politics is too important to be left to politicians.

Africa Today: Since then, you have taken on a new role: perhaps it could be described as that of watchdog of the new government led by President Mandela? You recently warned South Africans not to permit themselves to be "subservient lickspittles" - can you explain what you meant by that?

Tutu: We have come out of a situation where, because of a government that was increasingly authoritarian and which used all kinds of bullying tactics, quite a substantial part of our media were sycophantic. They were scared. A whole array of laws were introduced which made it very, very difficult for them to operate. There were things that they were often not allowed to report on. Now looking back, it was actually quite ridiculous that you couldn't say that so-and-so had been detained because the law said you couldn't. It was left to Church leaders, and we would quite deliberately say we were going to break the law, that we would tell the people that we knew that so-and-so had been detained or that such-and-such a thing had happened - and let the authorities take whatever action they wanted to take.

Many of those working on Afrikaner newspapers were party hacks, reproducing the government line. Even the liberal English newspapers were from the perspective of the Whites. They would refer to our leaders as "terrorists" and our organisations as "terrorist organisations" and we would challenge them to try and use at least neutral terms. So, what I meant was that we were served very badly by these sycophants who behaved in that way.

But we mustn't make the mistake of thinking that a government which is elected democratically, which is as hugely popular as this one, has been transformed into an angel. They remain human beings and can succumb to the temptation of abusing power. We must remember that they are not God and that when they stray from their responsibilities we must say so. The worst service we can perform for our country is for ourselves to be sycophants. Even Mandela is not God. He is a wonderful man, but he is frail. And the worst thing we can do for him and for our country is to turn him into a demi-God. When he makes a mistake, we must tell him.

Africa Today: You have been very critical of some of President Mandela's policies. Not very long ago this led to a battle of words between you.

Tutu: It was because we were his friends that we criticised him, that we said: "You were stupid to fall into the trap set by the Nats (The National Party)." One of the things they (the Mandela Government) did was to appoint a commission to look into the salaries of Parliamentarians and to recommend a huge increase. That may have been a justifiable increase - we don't know - but it was one of the first things they did and to have done it just then made it seem to our people living in shacks that they were just like all the other politicians - "They're just using us as steppingstones to get into power and enrich themselves." We told the government that that was bad, and we hadn't struggled in order to see them fail.

We passionately want them to succeed. If the day were to come when we no longer care about what they do, that is when they should really get worried. All we were saying was: "If we want our country to succeed, if we want democracy not only to survive but to flourish, then it must be that we keep them on their toes. But equally, we must be fair: when they do good things, we must praise them and tell them that they must be aware that our criticism is not just negative; it is positive - criticism that also acknowledges that they have done well.

Africa Today: So, you are a Christian in time of crisis and a Christian in time of relative peace?

Tutu: I am quite certain that, otherwise most of us would have found it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to have survived in the dark days. For me, obviously, it is Christianity that makes most sense of everything. But I am sure that people who are Muslims or Jews or Hindus would say their faith strengthened them and enabled them to survive the dark days.

Africa Today: One of the most important positions you held which not many people are aware of is that of Chancellor of the University of Western Cape. It is one of the most radical universities in South Africa and was in the forefront of the anti-apartheid struggle. Why the UWC? Couldn't it have been any other university?

Tutu: The simple answer is, they asked me to be their Chancellor. It has been an exhilarating time. It's quite extraordinary the number of people who had been associated with this university who have subsequently gone into government or are playing an important role. It seems to have been a wonderful nursery for preparing people for that.

In the bad old days, one never knew what might be happening: one might get a call to say that the police were on the campus, shooting tear gas cannisters into students' residences. We would have to dash over there to see what we could do. When one talks about these things now it almost seems as if we are making them up.

UWC did something that was important. The administration took over what was intended to be a Coloured university and decided to turn it on its head by transforming it into a people's university. It became the intellectual home of the left in South Africa. In normal circumstances, a university should be open and unbiased. Important though that is, universities cannot become ivory towers - they have to align - and UWC decided it was going to align itself with the people in their struggle and try to become more and more the kind of institution which the majority of the people would recognise as their own. So, making me, a non-Coloured, the Chancellor of what had been intended as a Coloured university was a kind of statement of principle.

We were also the first university to give what you might call an ex-terrorist an honorary degree - Govan Mbeki was given an honorary degree soon after he was released from jail and at a time when it was unfashionable to do so. Again, we were the first university in South Africa to give Mandela a doctorate.

Africa Today: You are also someone with an incredible ability to coin words almost on the spur of the moment. "The Rainbow People of God" swings to mind, which became the immortal words with which the people of the new South Africa have been described. At the time you coined those words, what exactly was going through your mind?

Tutu: We had one of South Africa's first mammoth demonstrations on September 13, 1989, when about 30,000 people of all races marched from St George's Cathedral to Grand Parade opposite the City Hall. It was an incredible spectacle. People had just been killed after a racist election in which 80 percent of the people had been excluded. In Cape Town alone, at least 20 people had been killed protesting against this travesty and a lot of bystanders as well. We said we had to do something to express our revulsion. There wasn't a great deal that people could do, but people said they wanted to do something, so we called this march.

At the end of it, we were standing on the balcony looking at this mass of people below and I just said that they should raise their arms and wave. There were Whites, Blacks, Coloureds, and Indians - it was a tremendous sight, and the phrase just came: "The Rainbow People of God." The rainbow is a wonderful symbol; in the Bible it is a sign of God's promise that He will no longer destroy the world with water. It is a sign of peace and prosperity, a sign of unity in diversity. It just seemed right.

Africa Today: Being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize was a great honour. How was the prize money spent?

Tutu: Soon after getting the Nobel Peace Prize we set up in the US a "Bishop Tutu Southern African Refugees Scholarship Fund" which operated out of New York. It has now been wound down because there are no more southern African refugees. Namibia became independent and South Africa is now free, but it helped to put about 50 southern Africans through college. And within South Africa we also set up a trust which gives grants to good projects. We setup both of these with part of the Nobel Peace Prize money.

Africa Today: You have indicated that you will be retiring next year. What will you do in retirement?

Tutu: I have got a professorship at Emory University, Atlanta. l will be there for a year.

Africa Today: Now, can we talk about your mission to Nigeria? There was a lot of hope when you went there in April (1995) that you might be able to broker a deal with the Head of State, General Sani Abacha, which would release Chief Moshood Abiola universally recognised as legitimate winner of the 1993 Presidential elections but prevented from assuming office and subsequently jailed by the military and pave the way for easing the political tension. What exactly did you set out to achieve?

Tutu: We hoped that Chief Abiola would be released and that the restrictions on General Obasanjo former President of Nigeria would be lifted. That was the immediate objective of the mission on which l had been sent by President Mandela. But we also hoped that that would just be the first item in the process of loosening the logjam.

Nigeria is perhaps the most important country on our continent and not only on account of the sheer size of its population. It has played a very important role in the liberation of South Africa. I think, almost from the inception of the United Nations Special Committee Against Apartheid, the chairmanship was held almost exclusively by the Nigerian Ambassador to the UN. That showed the remarkable importance Nigeria attached to the liberation of South Africa. In a way, without the commitment from Nigeria, our struggle would have been a great deal more difficult - it would have taken longer.

One of the Nigerian ambassadors once said to me: "You know, by rights, we should not be wanting South Africa to become free because a free South Africa is going to be one of our strongest rivals. But we are committed to it that we don't care even if South Africa should become our rival for the leadership of Africa. We want to be involved in its struggle for liberation."

So, we owe a great deal to Nigeria. There are not many countries in Africa that has as many highly educated people. I became aware of this when I was studying at King's College, London in in the 60s. I had Nigerian friends, fellow students who were working for the PhDs. in subjects like electrical engineering. They were quite extraordinarily impressive. A good number of South Africans went to study medicine at the University of Ibadan, which became the best medical school in Africa. When I asked the Dean how they had achieved this, he explained how they had appointed Whites to all the important positions in the school and sent the Nigerians to Britain and other places; encouraged them to get all the qualifications they could; to come back to Nigeria and to understudy the White people.

This they did and these highly qualified people, who had fellowships from places like the Royal College of Physicians or Surgeons, soon took over. They even had some of the best theologians, people like Professor Bolaji Idowu former Head of the Methodist Church in Nigeria.

So, I said to General Abacha that we in South Africa don't want to compete with Nigeria for the leadership of this continent, but we are jealous of the continent's reputation. The fact that the Giant of Africa is in the state that it is, in terms of its human rights record and the whole question of democracy, this has had a horrible impact on all of us. That is because we Africans are then dismissed by the rest of the world on the grounds that, if the leading nation is like this, what hope is there for the rest?

Therefore, the hope was that General Abacha would respond to the pleas from President Mandela to release Chief Abiola and that would then be part of the process of normalising the situation in Nigeria.

make any commitments to you?

Tutu: What kind of "commitments" did they make. They said Chief Abiola's situation would be determined by the courts! Of course, one knew that when negotiating in a situation of that sort, there are retorts that can be made - clever shots at the other's expense. But I hadn't gone there to score points or play marbles. l could have scored any number of points if I'd wanted to, but I had gone there on a very serious mission.

I found Abiola in a desperate state, emotionally. Maybe not physically, I don't know. His doctor says his physical condition was something that caused concern. But I know that his psychological state was very worrying. Here was someone who said he really didn't mind if they released him from where he was, provided it was to his house, even if they imposed restrictions on him there. He would be willing to fly doctors out from England to come and treat him at home.

Now that wasn't said lightly, considering a few months previously he was saying he was not going to accept conditional release.

Africa Today: Did the Chief realise the implication of what he was saying and how did he explain why he had rejected the bail offered him by the military government?

Tutu: l questioned him very closely. I said: "Are you aware of what you are saying - that you are ready to accept conditional release?" And he answered: "Yes." I then conveyed his wishes to the military government through the Foreign Minister.

On the bail issue, General Abacha had said in the meeting we had with him that Abiola's alleged crime was not bailable, but they had been ready to ask the court to grant him bail. However, the General claimed that at that time, Abiola had refused bail.

We put this to Abiola, and he said it was not true. He had not rejected bail. What he had said to them was that, since he did not have any legal training, he wanted his lawyer to look at the conditions of the bail so that he could advise him on what to do. Abiola said that the military took that as him turning down the bail offer. But he said to me quite categorically that that had not been his intention.

Africa Today: Are you disappointed that despite your appeal to General Abacha on behalf of President Nelson Mandela for the release of Chief Abiola, the General has done nothing since you left?

Tutu: The way things have gone couldn't be worse. I am disappointed because in a way they have rebuffed Mandela. I said to them: "Can you imagine what the reaction is going to be? Jimmy Carter (former United States President), a white man, comes and talks to you and you gave him some of the things that he asked for. I come, sent by a Black President, highly regarded throughout the world, and I go back empty handed. Can you imagine the implications?"

And I said to them: "Be aware that he (Mandela) is under considerable pressure to take a public stand on this Nigerian situation. You should know that the day he does that, the sanctions movement against Nigeria will take off like nobody's business. The Randy Robinsons (Mr Robinson is president of the American group, Trans-Africa, lobbying the Clinton government to impose sanctions on Nigeria) are just waiting to get Mandela's support and approval. So do something.

I don't know whether they themselves are desperate. Their own appointed "Constitutional Conference" actually took a stand, by putting a deadline for the ending of military rule; so, they had to resort to "persuading" it to withdraw and now the Conference has said Abacha can go on as long as he likes, and he can be the one to decide when to go.

Africa Today: What was the atmosphere like when you had this discussion with General Abacha? Did he show any appreciation of the international community's concern over the sad situation in Nigeria? How seriously was he taking what you were saying to him?

Tutu: When I was sitting there, I said to myself that if these guys had White skins and spoke with Afrikaans accent, I would have said to them: "I have heard all what you are saying before."

It was really uncanny. The sounded just like the apartheid Afrikaners when we used to go to see them, and they would say: "The country is peaceful" and actually imply that they were popular! Now, this general was saying in effect: "It's only a clique, like Abiola, Obasanjo, and others, who are causing trouble." I didn't know whether to laugh or cry.

Somebody said to me: "In Nigeria, you have to join the army if you want to be a politician." I replied: "But this is a great country. Nigerians have done incredible things. It's still a miracle how Nigeria holds together. It is a point of pride for us that Nigeria - despite the Biafran civil war, which we hope was some kind of aberration - has disproved the assumption that, because people are of different tribes, they cannot in fact cohere.

Africa Today. Would you like to return to Nigeria to do a follow-up?

Tutu: I have said to President Mandela that he should get in touch with Abacha and ask him: "What are you doing?" We'll take it up from there.

Africa Today: Is President Mandela likely to go public on the Nigerian issue and when?

Tutu: We are going to have to wait and see what happens. Meantime, it's not doing our continent any good and it is not doing our country any good. People will say: "You see, Mandela has no real clout. Tutu has no real clout..."

*This interview was first published in the September/October 1995 edition of Africa Today. It is reproduced in this edition to commemorate the death of the great man - Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu, born 7 October 193; died 26 December 2021.

Comment on this story